A teacher verbally explains to a student the math concept of ‘borrowing’ in subtraction. He explains it several times and the student still doesn’t understand. Then the teacher draws a diagram that more explicitly represents that the ‘3’ in the tens column really represents a ‘30’. Suddenly the student understands.

The teacher thinks, ”Ah-ha! This student is a visual learner. Once I drew the diagram he understood.”

What is the learning style myth?

The concept of learning styles has been around since the 1940’s when the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator started becoming popular. As the story above illustrates, it suggests that people have preferred ways of learning. The implication then is that, as educators, if you can teach in a way that’s consistent with the student’s style, he or she should learn better.

Most of the learning style theories are ‘type’ theories that classify people into distinct groups, based on self-assessments, as opposed to assigning graded scores on different dimensions, which is based on testing. These are some of the most prevalent learning style theories:

- VA(R)K – Visual, Auditory, (Reading), Kinesthetic

People have inclinations towards each of these. - Howard Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences

People have different kinds of intelligences (spatial, linguistic, logical kinesthetic, musical, interpersonal, intrapersonal, naturalistic and existential) rather than one type of IQ (intelligence). - David Kolb’s Learning Styles Inventory

A set of learning styles (converger, diverger, assimilator, and accommodator) based on preferences for abstract vs concrete and active vs reflective learning.

Myers-Briggs Type Indicator [MBTI] and other personality assessments are similar to learning style theories. While they don’t focus on learning specifically, they focus on answering the question, “What type of person am I?” In doing so, and because of their broad-sweeping success in mainstream society, they promote the general type-based learning-style assessments.

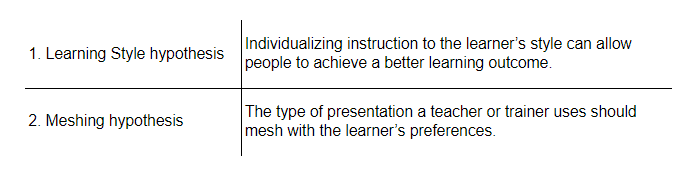

These theories suggest two things1:

What does the research say?

There is a large body of literature and articles on learning styles. In addition, there is a thriving commercial enterprise, which further promotes the importance and value of assessing learners. When weeding through all the material, however, it becomes clear that there is very little scientific evidence proving that learning styles exist and should guide the approach to instruction. There are only a handful of research articles that study the two hypotheses above. One2 that showed some support for the above hypotheses had a questionable methodology. Contradictory data was suspiciously excluded from the conclusions. The other well-researched studies3 show either inconclusive or contradictory evidence for the learning-style hypothesis.

Let me pause for a moment because I think it’s important to make a distinction between what the above research says is false and what research is true. Research has found both of the following to be true:

- People have preferences for how information is presented to them.

- This is often referred to “existence of study preferences”. It is well-researched and not disputed. 4

- However, the implications of such preferences for educational practices are minimal. Having a preference (and having assessed this preference) doesn’t inform which instruction would be helpful.

- People have aptitudes for different types of thinking and processing different types of information.

- Louis Thurstone5 proposed ‘primary mental abilities’ (e.g., verbal comprehension, word fluency, number facility, spatial visualization, associative memory, perceptual speed, and reasoning).

- While there is strong evidence supporting that people have specific aptitudes, there is no evidence that providing different groups with different type of instruction increases their learning or performance on a test.

So, there is researched-based support for individual preferences and aptitude, but not for adjusting learning approaches accordingly.

Where we ‘trip up’ is that we conflate people’s preferences for receiving information and their aptitudes for thinking and processing, with the idea that tailoring our approach to instruction will help them learn better.

Am I “splitting hairs’? Maybe, but I think it’s this confusion that perpetuates the myth of learning styles.

Why does the myth persist?

Some adjacent concepts are true

I think there are several reasons the learning style myth continues. The first reason is touched on above. There are elements related to learning that are true. People do have a preference for how information is presented to them. They do have different aptitudes for thinking and processing information. However, receiving and processing information isn’t learning. Let me repeat that:

Receiving and processing information isn’t learning.

Learning goes beyond simply remembering facts. Learning is our ability to add meaning to the facts, apply information to new situations, analyze it, evaluate and create something new with that information.

Commercial enterprise

Another reason the learning myth persists is the robust commercial enterprise that supports it. Kolb Learning Style Inventory (LSI) by Korn ferry, Honey and Mumford’s Learning Styles Questionnaire (LSQ), and Canfield Learning Style Inventory (CLSI) have a huge marketing presence espousing the benefits of knowing one learning style and adapting according.

Full disclosure: I am a licensed DiSC partner, and offer the full series of self-assessment-type products. I see value in them to help people understand themselves and others and to create smoother working relationships. I admit it’s a fine line between helping people develop insights and appreciating differences while not ‘pigeonholing’ them with broad generalizations, including how they learn.

Appeal to parents and students

The concept of learning styles and the idea that the type of presentation a teacher uses should mesh with the student’s preferences is strongly rooted in the school system. The seed is planted early and then grows throughout public school and even into higher education institutions.

The appeal is that because every child is unique, everyone has the potential to learn effectively and easily if the instruction is tailored to their learning style. If someone is failing in school, children and parents can hold the educational system responsible for not providing the correct instruction. It’s more comfortable to lay the fault with the teacher than it is to lay the fault with the child.

[Even writing that last sentence felt uncomfortable. The child is at fault? How can that be – they’re just children! But, there it is, learning style is strongly rooted in my psyche too.]

What nuggets from this are helpful?

If you’re left wondering what you should do now, don’t ‘throw the baby out with the bathwater.’ Remember, there is research that is helpful in guiding how we design and deliver training.

- People have preferences for how information is presented to them.

- People have aptitudes for different types of thinking and processing different types of information.

In addition to the above, there is research6 on ‘dual coding’ that suggests everyone benefits if visual information is layered over with linguistic information. Presenting information visually and verbally increases memory capacity over presenting information just verbally. Which is what happened with our school teacher explaining how to ‘borrow’ in subtraction.

Here are three techniques to incorporate into your training design to improve learning.

- Present information in different ways.

Incorporate the dual coding research to combine verbal and visual approaches to increase memory capacity. - Align the type content with how you present it.

For example, if you’re explaining geography, present it visually as a map. - Take the time to get to know your learners.

Design the course around the participants prior knowledge of the topic7. For example, someone new to their role will need more a direct and guided approach; whereas, an experienced employee would be frustrated by that slower pace and would prefer a targeted design.

1 Pashler, Harold, Mark McDaniel, Doug Rohrer, and Robert Bjork. Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence. Psychological Science in the Public interest, Vol. 9, No. 3. December 2009. 105-119.

2 Sternberg, R.J., Grigorenko, E.L., Ferrari, M., & Clinkenbeard, P. (1999). A triarchic analysis of an aptitude–treatment interaction. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 15, 1–11.

3 Cited in Bozarth, J. (2018). The Truth About Teaching to Learning Styles, and what to do instead? The Elearning Guild. 1-37.

4 Pashler, Harold, Mark McDaniel, Doug Rohrer, and Robert Bjork. Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence. Psychological Science in the Public interest, Vol. 9, No. 3. December 2009. 105-119.

5 Thurstone, L.L. (1938). Primary mental abilities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

6 Cuevas, Joshua, and Bryan L. Dawson. “A test of two alternative cognitive processing models: Learning styles and dual coding.” Theory and Research in Education, Vol. 16, No. 1. September 2017. 40–64.

7 Cook, David A. “Revisiting Cognitive and Learning Styles in Computer-Assisted Instruction: Not So

Useful After All.” Academic Medicine, Vol. 87, No. 6. June 2012. 778–784.

In case you missed it

I’ve shared some additional posts online. Here they are in case you missed them.

- Brinkerhoff – an alternative to Kirkpatrick for training evaluation – (video post)

- Updated analogy for developing others – Chef, home cook and caterer – (video post)

- Design guidelines keep individual courses consistent in a learning curriculum – (video post)

Curious to learn more?

I specialize in learning design and learning strategy. Here are some resources to learn more:

- Design for a Digital Age program – 2 month self-study and online program to design an online course for your organization (link)

- Facilitate in a Digital Age program – 1 month self-study and online program to integrate adult learning best practices and the latest technology to deliver a seamless online course. (link)

- Online Design webinars – free 60-minute sessions with online design tips and ideas to elevate your online programs (link)

- Learning Strategy webinars – free 60-minute sessions with models to get started with creating a learning strategy (link)

- Learning Strategy consulting – email me! info@performancematters.ca